Why is Defra Launching a Major Peatland Evidence Review Now?

- Andrew Gilruth

- Dec 1, 2025

- 5 min read

Many members and land managers will have seen that the IUCN UK Peatland Programme has been commissioned by Defra to lead a substantial, two-year review of the scientific evidence on peatlands.

This work will run from late 2025 through to 2027, producing new topic papers covering carbon science, peat hydrology, climate impacts, restoration techniques, grazing effects, water quality, flood risk and more.

This is an important and respected piece of work. But its timing naturally raises questions for those involved in the day-to-day management of our uplands.

A review of this scale normally informs policy - yet it begins only after major policy decisions have been taken

The new evidence review will examine many issues that sit at the heart of current peatland policy:

1. What is the net greenhouse gas impact of forest-to-bog restoration?

Many peatlands were planted with forestry decades ago. Restoring these areas back to open bog involves felling trees, removing drains and allowing peat to re-wet. This review will try to work out whether this whole process reduces or increases greenhouse gas emissions overall. This will include the carbon stored in the original trees, emissions from machinery and the long-term behaviour of the restored bog.

2. How do the biogeochemical processes in degraded peat change with rewetting?

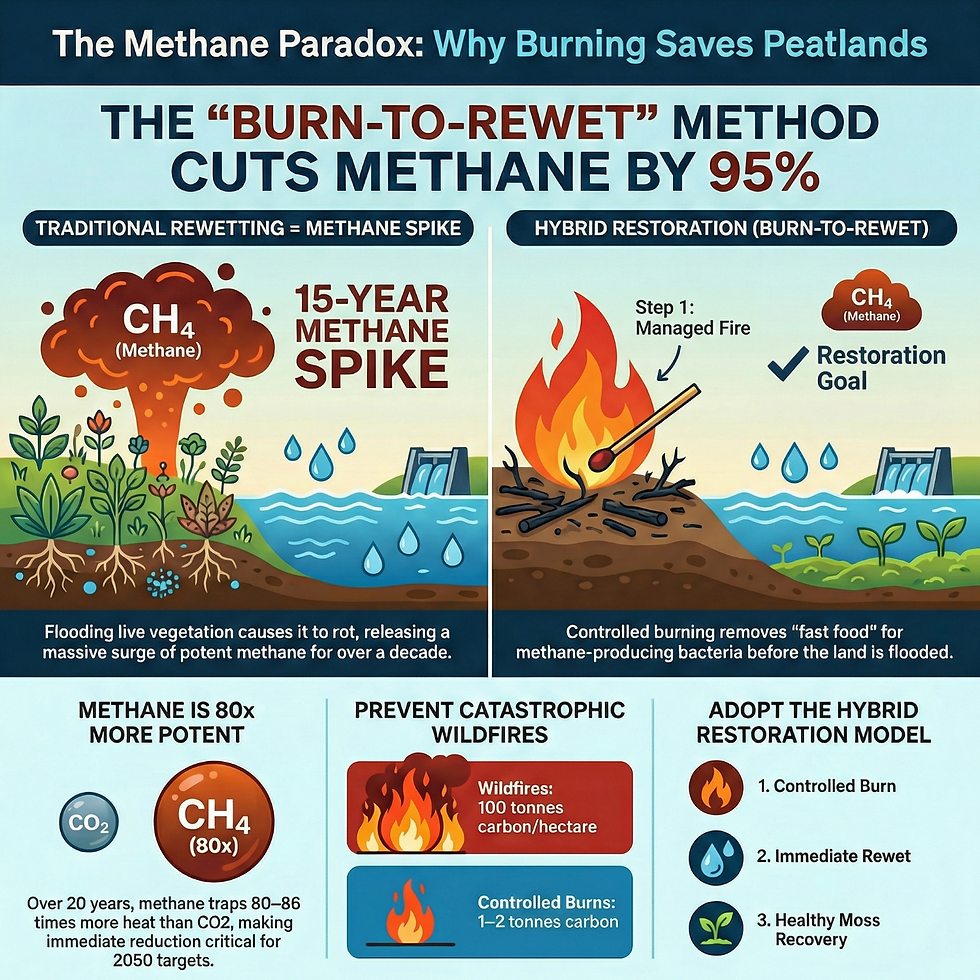

When peat dries out, oxygen gets in and the peat starts to decompose, releasing carbon. Rewetting stops this, but can also increase methane in the short term. What actually happens inside the peat when we re-wet it, and how do emissions change over time? It will help clarify whether rewetting always reduces emissions, or whether results vary site by site.

3. At what depth of peat does our understanding of natural chemical processes cease to apply?

Most peat research focuses on the top layer of peat, where plants grow. Much less is known about deep peat. Do the scientific assumptions used today apply to deep peat as well, or is deep peat behaving differently? This matters because many policies (including burning rules) rely on peat depth, yet deep-peat behaviour is poorly understood.

4. What are the greenhouse gas emissions of the peat restoration process itself?

Restoration work uses heavy machinery, materials, transport and sometimes disturbs peat. This question will calculate the emissions caused during restoration activities, not just the benefits afterwards. In simple terms, does restoration itself release a lot of carbon, and how long does it take to “repay” that carbon cost?

5. What is the lag time between rewetting/restoration and a return to carbon sequestration?

Even after rewetting, a peatland doesn’t immediately start storing carbon again. It may take years, or decades, before it becomes a net carbon sink. This review will ask how long does it actually take before restored peatland starts absorbing more carbon than it emits?

6. What are the most probable impacts of climate change on peatlands?

Hotter, drier summers and more intense rain will affect peatlands in different ways. This review will look at how will peatlands behave in the climate of the next 30 to 80 years?

whether healthy bogs will stay wet enough

whether degraded bogs will get worse

how carbon storage might change

the increased risk from wildfire, drought and extreme weather.

7. What is the role of peat restoration and rewetting/partial rewetting in climate adaptation?

This question is not about carbon, but about resilience. The review will try to understand how peatland restoration fits into wider climate-adaptation planning:

Can restored bogs help with flood management?

Do they hold water better in droughts?

Are they more or less vulnerable to wildfire?

8. What are the impacts of grazing on peat?

Livestock and wild animals can affect peat by trampling, grazing vegetation, or altering water movement. But grazing can also maintain habitat structure. This review will examine what types and levels of grazing help peatland condition and what types cause damage.

9. Are there degraded peatland sites which are considered unrestorable?

Some peatlands have been so altered (drained, eroded, afforested, converted to farmland) that restoration may not be feasible or cost-effective. Are some sites too damaged to restore, and if so, what should policy do about them?

10. What are the impacts of peat restoration on water quality, things living in it and river health?

Peat restoration affects the colour of water, sediment, dissolved organic carbon and aquatic life. This review will investigate whether restoration improves or worsens water quality, and under what conditions.

11. What are the impacts on water quality of raising and maintaining a higher water table within lowland agricultural peat soils?

Lowland farmland on peat drains water to stay productive. Rewetting could reduce emissions but might change water quality and farming conditions. This question explores what happens when you raise water levels on peat used for agriculture?

12. What are the impacts of upland and lowland peat restoration on flood risk and can these be quantified?

Restoration is often said to reduce flooding, but evidence varies. This question asks if restoration reliably reduce flood peaks, and are the benefits measurable and repeatable across different catchments?

13. How can the non-carbon benefits of peat restoration be quantified and monetised?

Peatlands provide biodiversity, water regulation, cultural value and landscape benefits. Is there economic justification for peatland restoration? This question will look at:

how to measure those benefits

whether they can be valued financially (eg natural capital accounting)

These are precisely the scientific questions routinely cited as justification for tighter controls on land management, including burning. Yet the review designed to answer them is only starting now, months after the conclusion of the 2025 consultation and the laying of new burning regulations.

For many land managers, this poses an understandable question:

If this review is necessary to strengthen the evidence base for policy, why was it not completed before the latest regulatory changes?

Defra’s stated purpose: to make the evidence “accessible to a policy audience”

The IUCN documentation is clear that the intention is to provide a high-quality synthesis specifically for policymaking. Drafts will not be available until late 2026, and final materials will be presented in April 2027.

That timetable inevitably means that neither the 2025 consultation nor the 2025 Regulations could have benefited from this upcoming body of work. Members may reasonably wonder whether earlier synthesis, of the kind now being commissioned, might have provided a firmer basis for recent decisions.

No criticism - but legitimate questions

It is important to stress that commissioning a review of this scale is positive. The peatland evidence base is complex, often contested and continually developing. Bringing together experts across the UK and Europe is a welcome step that should benefit everyone with an interest in peatland conservation and upland management.

However, given the reliance on scientific claims within the recent regulatory process, many in the sector will naturally ask:

Why is such a fundamental review being launched only after major policy decisions?

Shouldn’t the answers to these questions have been available during the consultation period?

How will Defra approach policy if the forthcoming evidence differs from assumptions used in 2025?

These are fair and constructive questions, especially for those who must operate within the regulatory framework.

What this means for members and land managers

The MA will continue to engage with Defra and with the IUCN review team to ensure that practical land management experience is properly represented. We will also keep everyone informed as the working groups are formed and as opportunities arise to contribute expertise.

The key message is that a major government-commissioned evidence review is only just beginning, even though policy changes have already been implemented.

It is entirely reasonable for the land management community to seek clarity on how Defra intends to reconcile those timelines.

We will provide further updates as soon as more information becomes available.

Stay Informed

📧 Keep updated on all moorland issues - sign up for our FREE weekly newsletter.