FAQs: MA Position Statement on Controlled Heather Burning

- Rob Beeson

- Jul 9, 2025

- 9 min read

In our recent position statement, we argue for the continued use of controlled heather burning as a vital tool for moorland management in the UK, amidst ongoing debates and proposed restrictions. Such vegetation management is crucial for lowering wildfire risk by reducing fuel loads, particularly given increased public access and climate change.

The current scientific understanding of how controlled burning impacts carbon storage is complex and evolving, but evidence shows that it can contribute positively to long-term carbon sequestration through charcoal production and vegetation regrowth.

Furthermore, we believe that this practice is beneficial for maintaining biodiversity by creating varied habitats and supporting important upland bird species.

The current policy proposals to restrict burning often lack robust evidence and may lead to detrimental outcomes, and we advocate instead for an adaptive management approach that recognizes the unique characteristics of different peatland sites. To accompany this position statement, we have compiled the following series of common questions and our responses.

How clear is the science on how heather moorlands should be managed?

What evidence is there on the long-term impacts of cutting as an alternative to burning?

How does controlled burning impact carbon storage and greenhouse gas emissions?

Why is Defra proposing to increase restrictions on controlled burning?

Does the MA support controlled heather burning?

Yes, when it is carried out safely and in a suitable place. We advocate for the use of small patches of cool burns with appropriate return intervals. No single management technique is suitable all the time on every site, but controlled burning is a valuable tool in some circumstances.

Why is this so controversial?

The debate stems from concerns about the possible environmental impact of burning as a tool for vegetation management, particularly its effect on peatlands and carbon emissions, alongside its cultural and historical significance. There is a lack of scientific consensus on the best management practices for different peatland types, leading to a risk that policy changes may be made without a robust evidence base.

How clear is the science on how heather moorlands should be managed?

The overall effect of burning on peatlands is unclear and is still evolving, with significant areas of uncertainty and ongoing debate among experts. There are significant weaknesses in the evidence base, due to insufficient, often short-term, contradictory, or unreliable evidence. Therefore, robust conclusions about ecosystem service impacts like carbon storage, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, flooding, and water quality are not yet possible.

There is not yet a scientific consensus regarding the best way to manage different areas and types of peatland and some experts express concern that policy may be "running ahead of our knowledge". Given these complexities and knowledge gaps, we call for an adaptive management approach, alongside more robust, long-term, site-specific research, rather than implementing blanket policies prematurely.

Is the risk of wildfire higher if heather is not managed?

Yes, the risk of severe or uncontrollable wildfire is considered to be higher if heather is not managed. Regional Fire and Rescue departments also agree that allowing fuel loads to build up increases wildfire risk and makes control more difficult. Destructive wildfires are becoming increasingly common, and high fuel loads, combined with increased public access and climate change leading to drought conditions, make uncontrollable wildfires more likely.

The Future Landscapes Forum, a group of experienced academics and practitioners, states there is "no clear evidence nor a scientific consensus to support a blanket ban on controlled burning", implying the need to retain a variety of different management tools.

What is rewetting?

Rewetting is the reversal of artificially drier conditions on moorland that are the result of human activity. This would include blocking up historical drainage to raise the water table, as well as addressing vegetation changes, for example revegetating bare areas to stabilise peat erosion, and managing grazing patterns.

Does the MA support rewetting?

We fully support rewetting to reverse the negative impacts of historical drainage as part of peatland restoration, but we suggest that there are limits to what it can achieve as a result of site differences, and we should not rely on it as the sole approach to vegetation management.

We consider that removing drainage and managing vegetation can help to return an area to its current natural wetness potential. Water flow is affected by many different factors such as slope, the depth of the peat, what lies under it (e.g. bedrock vs free draining subsoil) and we have to work within these natural limitations of the site; we cannot increase rainfall or change the natural aspect of the area.

There are many moorland peatlands which are fully rewetted in terms of drain or gully blocking, and areas which have never been drained, but which cannot achieve a water table at or close to the peat surface year-round.

While there may be an assumption that this may or must have been the case historically for the peat to have originally formed, there are many reasons why it may not be realistic to expect to recreate those conditions now, including changes in climate.

Will rewetting limit heather growth?

While heather growth can be limited in extremely wet situations, it usually requires a water table at or very near the surface all the time, year-round. The expectation that rewetting alone will achieve this level of wetness and limit heather growth everywhere is a point of significant uncertainty and concern.

We believe that this assumption is mistaken because of ecohydrological differences between peatlands. There is a clear natural limit to how wet different sites can become based on various factors such as slope and rainfall; therefore, not all peatlands have the potential to become wet enough for heather growth to reduce or die back. This means that for many sites, rewetting alone may not sufficiently restrict heather growth.

In summary, we believe rewetting is valuable, but that it alone will not be sufficient to limit heather growth across all peatland sites. There are significant uncertainties and concerns about its effectiveness in reducing fuel loads and wildfire risk in a suitable timeframe, therefore we support adaptive management where rewetting is not enough.

Is cutting as effective as controlled burning?

There is not enough evidence to compare the risks and benefits of cutting heather versus controlled burning, and therefore, it's not entirely clear if cutting is as effective as controlled burning.

Far less is known about the impacts of cutting compared to burning. While some negative impacts from cutting are becoming apparent, ongoing research in this area is needed. Both cutting and controlled burning lead to carbon loss from above-ground vegetation.

With cutting, this carbon is released as the left-behind brash decomposes over time, a process that is slower but extends over a much longer period than the immediate release from burning.

One long-term study, initiated by Natural England and Defra, estimated that areas managed with controlled burning were a carbon source (released more carbon than absorbed) for 5-7 years before becoming a carbon sink again. In contrast, areas managed with cutting were a smaller carbon source for 7-9 years but, once they became a carbon sink, absorbed only around half the carbon compared to areas managed with controlled burning.

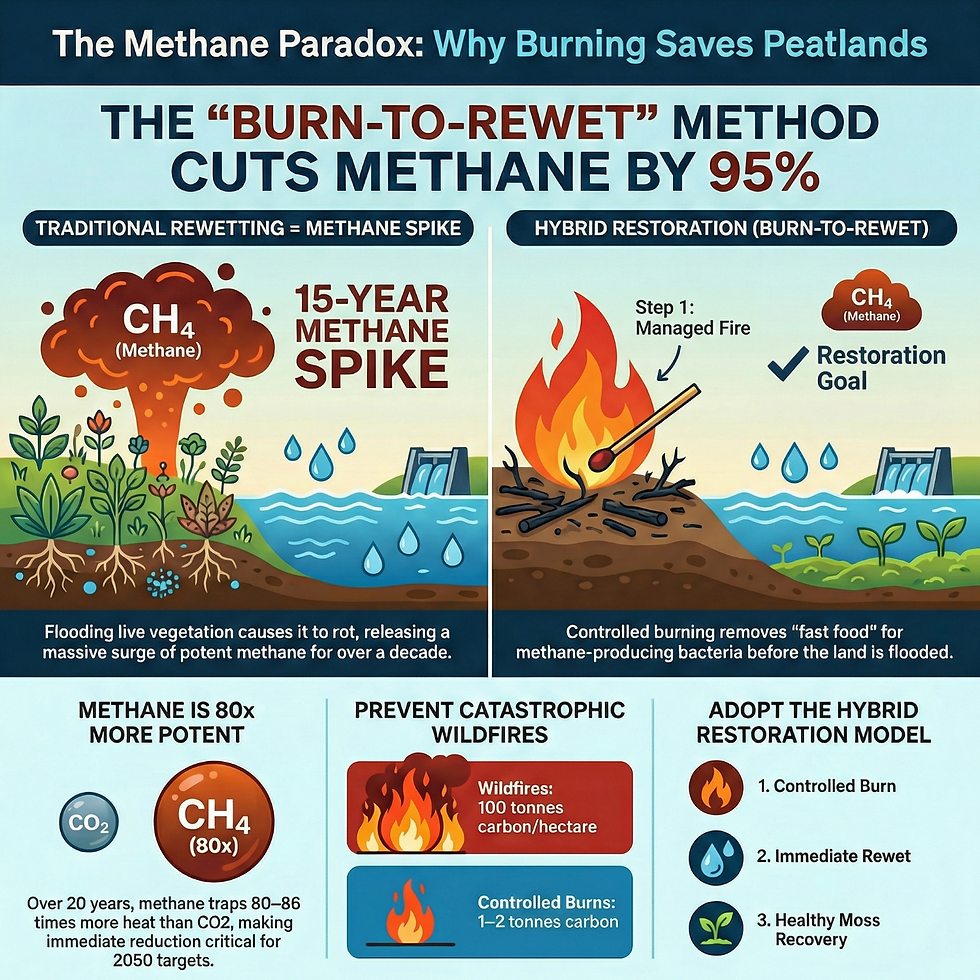

The charcoal (pyrogenic carbon) produced by controlled burning is an effective and important component for long-term carbon storage on peatlands because it is very long-lasting and resistant to decomposition. It may also suppress peat decomposition and reduce methane emissions. This specific long-term carbon storage mechanism is associated with burning, not cutting.

We support an adaptive management approach, allowing land managers to select from a range of suitable techniques, including both controlled burning and cutting, as appropriate for different sites. Where a site cannot be sufficiently rewetted to restrict heather growth, vegetation management, chosen appropriately for the site (cutting or prescribed burning), should remain an option.

What evidence is there on the long-term impacts of cutting as an alternative to burning?

There is very limited evidence and considerable uncertainty on the long-term effects of cutting.

Is controlled burning damaging to the environment?

Whether controlled burning is damaging to the environment is a complex question with an evolving scientific evidence base.

An initial clear effect of controlled burning is the immediate loss of carbon from above-ground vegetation which is intentionally removed during the intervention. This carbon is released in smoke from the combustion.

This immediate carbon loss may also be accompanied by other routes such as subsequent slower rates of peat accumulation, carbon loss through watercourses in dissolved or particulate organic carbon, and increased vulnerability to erosion on small managed areas.

However, carbon losses from burning are usually absorbed again as vegetation regrows faster after the management. Ash fertilization following burning can mean that heather grows back more quickly and sequesters more carbon during this regrowth phase compared to cut areas or those not managed. We know that areas managed with rotational burning can and do store carbon and grow peat over time.

While controlled burning involves an immediate release of carbon, it plays a crucial role in mitigating the greater environmental damage of uncontrollable wildfires and it can have benefits for long-term carbon storage (via charcoal), enhanced carbon sequestration, and biodiversity. Some authors and organisations present the view that controlled burning always has a negative impact on carbon uptake and storage, but we believe this narrative doesn’t reflect the whole evidence base.

How does controlled burning impact carbon storage and greenhouse gas emissions?

The impact of controlled burning on carbon storage and greenhouse gas emissions is complex and an area of ongoing research with limited long-term studies. Initially, burning causes an immediate loss of carbon from above-ground vegetation.

However, there are also counteracting increases in carbon uptake as vegetation regrows vigorously. A significant factor often overlooked is the conversion of some above-ground vegetation into charcoal (biochar). This charcoal is highly resistant to decomposition and contributes to long-term carbon storage.

Furthermore, evidence suggests that charcoal can suppress peat decomposition and reduce methane emissions by stimulating the conversion of methane to CO2. While initial carbon release is immediate, studies suggest that burnt areas can become carbon sinks again within 5-7 years and absorb more carbon than areas managed by cutting in the long term.

Why is Defra proposing to increase restrictions on controlled burning?

Defra are guided by a recent evidence review published by Natural England, which supports the narrative that all controlled burning is detrimental to peatland. The main increase in restrictions from these proposals is the suggestion that they should apply to all peat over 30cm in depths, rather than that over 40cm. This will vastly increase the area that the restrictions apply to.

Is this a sensible change?

It depends on your point of view, interpretation of the evidence, and opinion about the risk of wildfire.

There are no globally recognised definitions for peat or peatland, with a range of approaches used in different countries. Some advocate measuring peat depth, others use organic matter content as a metric. One recent paper quotes 16 different definitions for peat across 11 countries, finding that areas of “peat” were defined at depths ranging from 10cm to 60cm, with the most common threshold being 40cm, but the average being 30cm.

Furthermore, we believe that vegetation management is a critical tool to reduce wildfire risk, and well-managed controlled heather burning is invaluable in keeping fuel load low. We and others do not accept the narrative of Natural England’s Evidence Review that all controlled burning is detrimental, we believe the scientific assessment process was flawed, and the analysis of the evidence leaned towards supporting that pre-conceived view.

We are extremely concerned about the increased risk of uncontrollable wildfire and the devastating consequences, and we think that these changes will push that risk yet further.

What is the MA doing to challenge NE’s position?

We have prepared a robust response to Defra’s consultation, and we continue to publicise our views about the danger of the proposed changes. We are working with leading academics and other organisations to increase awareness of the entire evidence base in this area and inform key stakeholders.

What can I do if I am worried about fuel load?

Review and update your moorland management plan to ensure that it addresses fuel load management and wildfire risk. Consider the full range of options for vegetation management – including controlled burning, cutting, grazing and re-wetting – and decide which approaches are most suitable for different areas.

Check whether you will need Natural England consent before burning – this will usually be the case if the land is within a SSSI. Check whether you will also need to apply for a licence to burn from Defra – this will be the case if the site is on deep peat (>40cm deep) AND within a SSSI which is also an SAC or SPA.

You can check designation boundaries on Defra’s MAGIC Map. You may also wish to speak to neighbouring landowners and your local Fire and Rescue Service to discuss wildfire risk and fuel load management.

How do I apply for a licence to burn heather?

Defra has proposed changes to the rules on burning heather and consulted on them in spring 2025. At the time of writing (July 2025), under the existing rules you will need a licence from Defra to burn heather only if the site is on deep peat (>40cm) AND within an SSSI which is also an SAC or SPA. Defra guidance on how to apply can be found here.

Note that you will almost certainly need Natural England’s consent to burn heather on a SSSI, so you will have to make a separate application, and secure consent from NE before Defra will grant a licence.

The MA is preparing guidance for members on the licence application process and is also in discussions with Defra and NE about how the application process could be streamlined and simplified.